A CUPFUL OF WORLD

Monteisola Island, Italy, Summer 2023

By Nikola Popović

‘As big as oranges’, say the papers of Brescia. ‘The size of walnuts’, say those of Bergamo. On the road leading from Brescia to Lake Iseo, all the talk is about yesterday’s hailstorm. A sixteen-year mountain climber killed, her life cut short by a tree felled in the storm. Two people on the expressway near Varese dead after their car hit a lorry. So write the papers of Lombardy.

The previous night’s storm and a new one that has been forecast are the topics of conversation on the motorway leading from Venice to Milan and onwards to the lakes of Como, Lago, and Iseo. Service stations and motels are no caravansarais, those inns clinging to the sides of oriential thoroughfares, but even here, on the tarmac of the autostrada, any occurrence, either happy or infelicitous, is talked over. The icy pellets grow in the telling and the tragedy of the expressway is recast as melodrama or detective fiction. Meanwhile the summertime blizzard moves on, beating down on wheat stalks, crops, and vineyards. Cars are left with pockmarked roofs.

‘What you ought to do before a storm is wrap your car with a cover and a blanket, tuck it in like a child so it doesn’t catch cold’, says the skipper of the ferry sailing to the island in the middle of the lake, ‘only, your wife may get suspicious of why you’d need bedclothes in the boot.’ He cracks a smile, lighting a cigarette, another one wedged underneath his epaulette. In profile he is the consummate captain, with an ocean-going beam, but, when viewed head-on, he is more of a ferryman, a sweet-water banterer from Monteisola, the island in the midst of Lake Iseo. The papers print photographs: a drowned house, a felled tree, the expressway, ice pellets the size of fruits.

An adventurous peregrination

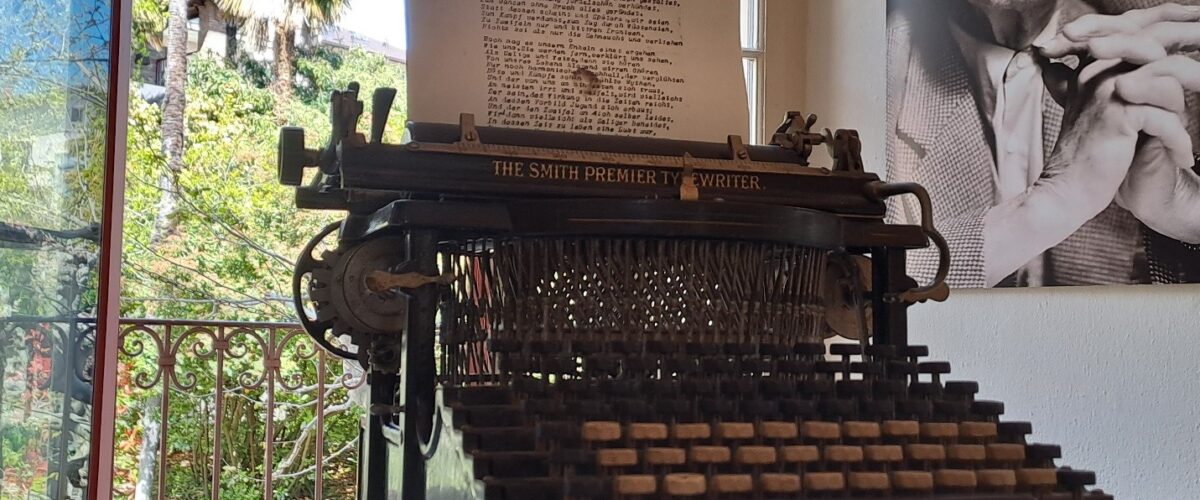

One travels in the company of memories and childhood reading, a baggage both literary and experiential carried by the wanderer. Arrival on the pier of Lake Iseo brought to mind Iron and Honey, a novel I translated after I had first met its author Ettore Masina. This first-person narrative of Venice in a time of plague and quarantine barges tells how a young man, travelling from Brescia to the city on the lagoon, became bogged down in uncertainty and risk: ‘I brought with me from Breno di Valcamonica a large load of timber and another one of ironmongery, having completed a venturesome three-month voyage fraught with dangers of all kinds, from highwaymen to landslip-prone paths to malarial swamps.’

Cities in tales are real up to a point, but a dreamlike quality soon takes over. In Masina’s story, historical episodes and Venice rock gently like a gondola does, characters and events shimmer in the dank lagoon. A love story woven into the novel begins with a word portrait: ‘A cape of black hair, smooth, reflecting a myriad colours, fell across her frail shoulders. In an instant, as our gazes met, she hurriedly withdrew, having given my companion a sign of recognition and a smile.’

In a story everything is an instant. Back in the present, in the neighbourhood of Brescia, Masina’s native land, I seem to hear again the voice of the great traveller telling me of the trade of the writer, how a life rich and full was distilled into prose, into fiction: ‘Every tale is an autobiography’. Done speaking, he takes a sip of the Barbera, a violet-coloured wine, then first recalls distant travels but is soon spinning a yarn of Lombardy, his homeland: the Valcamonica valley, known as the Valley of Signs for its prehistoric rock drawings, indigenous herbs, and an equally succulent dialect that, like the herbs, draws its strength from the soil.

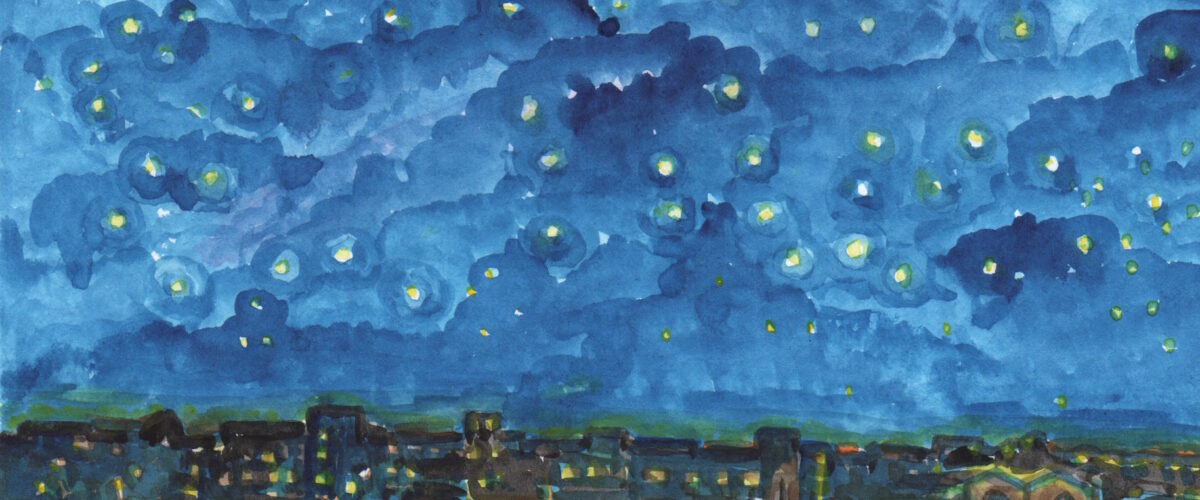

The book speaks of Venice, of floating quarantines in a season of plague, a time of death carts, firebrand preachers and radical prophets, when illness mowed down towns and villages, tangled love stories, and tumbled destinies as if in a whirlpool. The novel’s end brought another journey – the return to Brescia over mountain passes and snowbound paths, closing with flashes of light over Lake Iseo. Crystals of water and sky. Such is the tale Mesina tells in his book of Lake Iseo, of flickers of whiteness trembling on the water. It may lie in the north, but its water is softer and warmer than that of other lakes.

Terra firma

‘It’s all quiet now’, says the captain as we draw alongside the pier, ‘but come morning, with the first rays of life, all the lake and the island of Monteisola will come to life’. As he speaks he is every inch the island’s host, looking to unravel the whole tapestry of island and lake, layering in the same sentence air that carries the breath of the Alps and the Mediterranean, water that does the skin good, olive oil that is scarce just like everything else on the island is scarce, pinkish trout, carp and zander, and sardine of the lake, more delicious than the sea kind.

As they are tying down the hawsers and dropping anchor, the captain considers putting in a few more words, but the vessel is already coming to. Looking landward from the ocean sea, sailors call the shore terra firma, the solid ground. Says the captain of his island in the midst of the lake: ‘All that’s needed is here, this is where land is.’ There appear light-toned facades and a church steeple up on the hill, in a cypress wood. Even when no longer rocked by the waves, the body retains its own sensation of sailing.

It is quiet on the island, a storm is brewing. And here the first plump drops are already coming down on the pier, on the tables of the bar next to the ticket office, on the beads and necklaces that little girls sell. They bring them in hurriedly, the mothers calling from the balconies, from the houses right along the shore. A squadron of gulls flits overhead, the birds formed up in a diamond pattern against the sky. A little girl pauses to ask her mother: ‘Where are they going?’ An embroidered tablecloth where freshwater shells had been laid out just a moment ago is taken up by the wind and flutters in it like a tiny little kite.

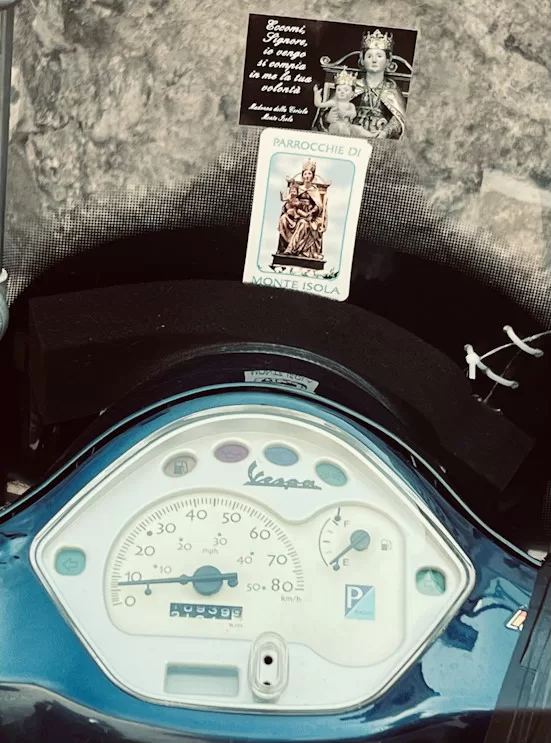

The morning after the rain

Last night there was a hailstorm on Monteisola and Lake Iseo. The turbulent water rocked the moored boats. Those who got there in time covered their greenhouses. Some of the island’s taxi cabs they were able to put under cover. The last few drops trickle down from the vespas leaned against the wall. Forked twigs on which salted fish is spread, taken in for the night, are brought back out into the early morning sun.

‘It’s a pity about the olive grove’, says our captain, puffing on a cigar. I meet him in a bar by the pier. He is looking at the lake that is not yet fully calm, the morning is clear and mild. Ducks and swans sail along the shore. ‘Look at them shaking their wings, they’re still sodden, heavy with rain.’ Then he lowers his gaze to take in the newspaper reports of ice balls that rained down as if they had been grenades.

Stories of the storm are briefly displaced by news of actual grenades bursting into shrapnel in a war that rages far to the east of Iseo and Monteisola. But even here, on the island, but for the storm, there would be talk of politics and divisions, of the flames of war, which would spread like fire in a field of wheat if they were to gain more force.

What will the year be like?

Just like with Masina’s novel, there comes back a memory of travel to an island in the south of Italy. It was the night before the premiere of an opera in Palermo. As intricate as a mosaic, Verdi’s story of the pirate Boccanegra was epically long, replete with history and tragedy.

‘Will there be amorous intrigue?’, an old lady asked her husband as he read her the digest from the playbill. In a pistachio-coloured three-piece suit, carrying a wooden walking stick with a brass swan’s head for its handle, peering through thick glasses suspended from a cord, he read quietly though clearly.

She, in a dapper chequered skirt suit, an amber brooch on her lapel, and wearing a flowery scarf from back in the day, the kind one would keep in one’s trousseau, listened, albeit following the rhythm of his speech more than the story itself. Then again: ‘Will there be amorous intrigue?’ ‘There will be, amore mio, there will be’, he replied.

The show was put on a year ago, just before the war started over there, to the east of the Mediterranean. After the opera, as drinkers’ pupils widened to exquisite liqueurs and strong espresso in the Sicilian night, words descended on the show, both the opera that had just ended, and the larger one that had just opened on the global stage. ‘Will the waves reach Sicily?’, wondered the Palermitani.

‘Will there be more storms, or was tonight’s tempest the last of the bad weather? What will the olives be like, how will the vintage turn out?’, wonder the people of Monteisola.

Speech and the marrow of the island

He is, right, the captain. The sardine of the lake is delectable, even more so than the sea kind, in it is the marrow of the island, they dry it salted on forked twigs of olive wood, the meat of the fish becomes imbued with the air of the Alps and of the Mediterranean. As Masina might put it, ‘Whenever you eat, pour yourself some wine from the same parts.’ To accompany fish, the islanders take Franciacorta, the wine of the Brescia region; with it they souse their mouthfuls, steeping in the vintage also their Lombard speech, which draws aromas out of the ground like the vine does, with a sprinkling of local, insular words, too.

When travelling, one’s being swells, ruminating on things it has experienced and read about. Chronicles, tempests, and stormy nights will become stories. There will be years of drought and those of rain, clear mornings, and stormy nights. There will be years of peace and those of war, when princes quarrel, but man is ever the same: all he would do is cross the water to the far bank and spread a cover over his olive grove when it rains. And all he wonders about is whether it will be a good year for his crops.

Everywhere alongside the road there are milestones, the wonders of our world. Over there, on the rocks of Valcamonica, the caveman left his traces: warriors with spear and shield, deer, horses. Birds fly in squadrons, in formations known only to themselves, looking for somewhere to rest on the other side. There are rivers and seas, lakes and islands, that are good for people. To the south is Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean, to the north is Monteisola, a small one, in the midst of Lake Iseo. The story is both land and pier, it slakes thirst and reinvigorates like wine, a cupful of world.

Translated by Uroš Vasiljević

Photos: Nikola Popović

About the author

Nikola Popović (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1979) is an Italian literature researcher and Italian language teacher in the Music Department of the Faculty of Philology and Arts (Kragujevac, Serbia). He has published Serbian translations of Ettore Masina, Simona Vinci, Valeria Parrella, and other authors, as well as numerous essays on contemporary Italian prose in Serbia and in Italy. He has authored essays on film, theater and literature, as well as fiction stories inspired by his travels in Lebanon, Ghana, Congo, and other countries.

He has published the following books: Priče iz Libana (“Stories from Lebanon”), Skice za plovidbu (“Sketches for Sailing”) and San Kosmosa Skaruha (“The Dream of Cosmos Scarooh”). He is the recipient of several literary prizes in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was editor–in–chief of the Bosanska vila literary review based in Sarajevo. His work has been translated into English, Macedonian, Hungarian and Portuguese.