AN EVENING BEFORE THE OPERA

Palermo, Sicily, February 2022

By Nikola Popović

“Will there be any love intrigues?” she asks as he is reading the synopsis of the opera from a theatre poster. He has put on his glasses hanging on a string, reading quietly yet distinctly, but she is more absorbed in the sound of his words than in the storyline. It is an intricate story, opera-like and entangled. The opera is Verdi and Verdi-style, epically long, full of historical plots and tragic elements.

Simone Boccanegra, a former pirate, becomes the Doge of Genoa, so he balances between the mob yearning for bread and betterment, and bickerings among nobles hungry for power. He meets his death at the hands of his adversaries; Boccanegra dies having emptied a poisoned cup, singing amid ships an aria full of longing about the days he spent at sea.

Judging by the opera plot, the Doge does not feel like going to war with another maritime power, the mighty Venice, as he could already see masts and trunks of ships in flames. The librettist from the time of Italian unification, when this theatre, Teatro Massimo in Palermo, was built, introduced into his text the words on common Italic soil, and how wrong it is to shed blood between brothers.

The opera storyline aside, the air of Palermo is full of sea salt, the city light is clear while colours are saturated, southern. The environment is full of colourfulness and shapes, like baroque facades of Sicilian churches. With the sound of their speech, movements and thoughts, the people of Palermo are immersed in such an environment.

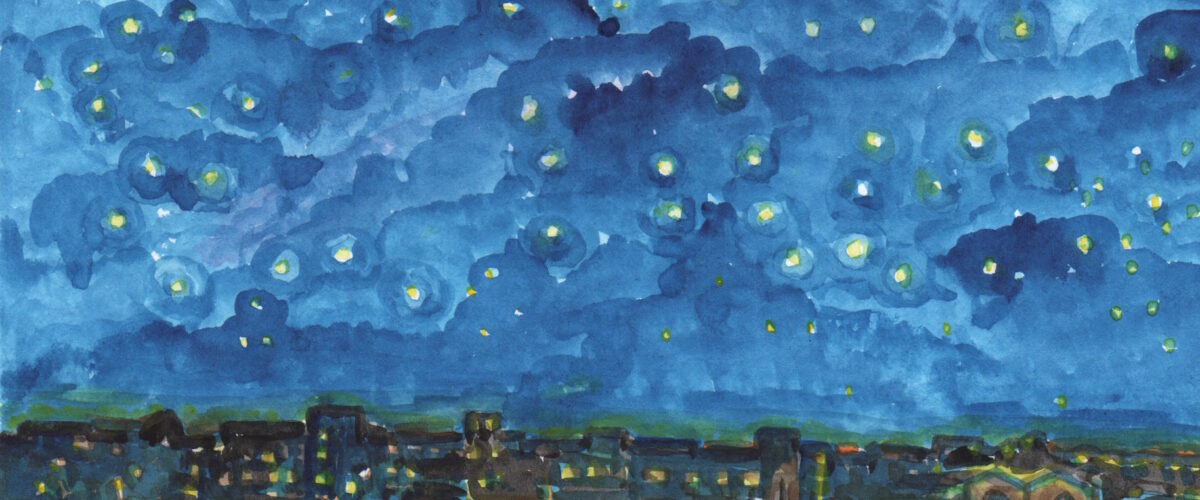

Donatella Gessoni, Notte stellata

*

He is wearing thick glasses and a Sicilian flat cap called coppola, made of wool, as evenings are still chilly. His suit is three-piece of greenish pistachio colour, the bow-tie is of floral pattern; he has leaned against the table a wooden stick with a brass swan-head handle. She is wearing a skirt suit resembling those worn by Queen Elizabeth, square and well-fitting, but it makes her petite frame look even smaller in appearance now that she is all wrapped in the fabric. An amber brooch on her lapel is of floral design, outdated, as the one kept in a bride’s trousseau.

And so I listen to these two elderly persons sitting close to me in a bar in the main square in front of the theatre before going to the opera, dressed in classic, old fashioned clothes. The rhythm of their speech is dignified, flowing like an opera overture. A waitress (a row of thick black eyebrows springs above the protective mask) brings coffee, a short pull espresso; next to each cup are almond cookies with pistachio and chocolate cream.

The café is now full, as the first performance after the premiere of Simone Boccanegra, which is still fresh at the repertoire, is about to begin. Some, such as these two elderly persons, are busy reading about the opera, discovering plots and finding relations between characters driven by passions of love and jealousy. Others think it is too late to read the story now, ahead of the performance itself, so they enjoy drinking coffee or liqueur with fruit or nut flavor; the aftertaste will remain during a three-hour opera.

*

This is what it looks like outside the theatre before the opera in the Palermo main square. It smells of perfumes and there is something concert-like, solemn in the air as if a ship is about to leave a port. The little old man is reading to his wife in a soft and calm manner a lengthy opera plot about a war with Venice that will or will not begin, about lovers and avengers. Through the sound of this opera tavern words are also heard about a war that is unfolding not in the opera, but in reality and has lasted for days in the east of the continent, between two Orthodox nations.

People of Palermo bring up in conversation the causes, consequences, warring states, their own Sicily after all. Sicily is far from the battlefield on the mainland, it is cast aside being an island, although on the dividing line of roads in the middle of the Mediterranean and no major event so far has missed it. The bar serves salted capers from Lampedusa, the southernmost island belonging to the Sicilian region, which is the arrival point for boats full of Maghrebis and all the others who have fled to escape danger.

The grand and global spectacle has begun, but here on the island where the echo of battles is perceived only like gentle waves of a faraway shipwreck, the little opera spectacle begins. Its libretto is based on real events just like any story, as Genoa used to be a maritime republic and Boccanegra used to be a pirate and its doge. However, stories, including this one, float on the surface of the sea, creating dislocated worlds, just like an opera performance is a life outside the real, great and global life, which is now filled with everything except cheerfulness.

Tenors, baritones, sopranos will start singing soon, human voice will be embraced by the rich timbre of the orchestra. The ship will sail away and sugar-filled dregs of coffee and liqueur will remain on bar tables. In the theatre box I can hear that question again: will there be love intrigues in the opera, in addition to noblemen’s quarrels and poisoning of the doge.

– There will be, amore mio.

*

Now in early spring not much sound is heard in Palermo in the middle of the night, only the sound of a carriage riding to Quattro Canti. It is the intersection of the city from where quarters go in two directions – towards the sea and to Monreale Hill, the see of the Bishop, overlooking the port and where the bus rambles through streets narrow and steep.

In Quattro Canti, a tourist, an American woman, has come up to a horse hitched to a buggy, caressing its white mark on the brown top of the head; the horse looks around in a calm manner, it is of Eastern breed and knows that its mane and tassels will catch the eye of everyone visiting Palermo, but hardly anyone would give a euro or two to the groom, who is folding tobacco and looking at the fountain, the church and the square, at everything standing still and passing by, not in the least surprised, just like his horse treads on the well-known path with a light trot.

Palermo is a city of wide streets and squares, where friends will shake hands and a man waiting for a woman will kiss the beloved lips. Men wear navy blue coats; women wear coats in the colour of whipped cream. Looking at them, one will see both Arabia and the Normans in their profile, peoples from all over the world and all Mediterranean pervasions that the city and the island absorbed in architecture, dishes and facial features.

The promenade is gleaming and clean. But, the moment one goes off the beaten track, streets are filled with garbage while neon lights of fast food restaurants and of shops selling plastic are different from a fairy tale place. One used to perfect images will find this annoying, but a traveller must remove the inessential from their perspective. Here, in quarters hidden from view, a more recent history lives and thrives through graffiti and drawings similar to comics. Overlooking from a mural is Judge Falcone with a Clark Gable moustache.

Life is throbbing at a quick pace of the south. A passer-by will see laundry hanging on the rope between two balconies and Palermo mammas, signoras as powerful as Juno, shouting each other’s names on the balconies with cactuses and fragrant plants. Between houses made of stone a smell of olive oil permeates the air; it is strong and made with love and care; there is also a whiff of roux made of garlic, rosemary and wine.

All around are markets vaulted by the blue sky alone. Fish, fresh from the sea, is placed on the grill. On the ice are shellfish, tiny clams, large mussels, swordfish split in two. A fish head covered in blood is pinned to the ice, like the sword in the stone. Dried tomatoes, capers, anchovies, sardines are added to pasta; fresh cheese and tangerine, pomegranate and carob are added to desserts.

In the harbour by the sea yachts and fishing boats lie anchored. Standing on the pier one can see a Vespa scooter which fell into the sea a long time ago; a colony of crabs has now settled on its wreck. The Vespa, once probably stolen and left by the sea is said to have been toppled by a gust of wind, ending up in the sea with its headlights turned on for quite some time.

On the barrels turned upside down fishermen are selling octopuses and squid, crabs and sea urchins, their coarse hands ravaged by the sea. The purple shellfish, hard from the outside, full of soft marine tissue inside, once fishermen’s food, is now a restaurant delicacy. “The urchin is expensive as it is the mating seasonʺ, says a fisherman this morning. “They are in short supply”, adds another. The urchin is known to live in crystal clear water only. The third fisherman says that there is more of that captivating Mediterranean savour in the spiky inhabitant of the seabed than in citrus fruits and capers, but few people want it. Sicilians and tourists alike now prefer milder, mellower flavours.

*

Palermo lulls a traveller, who feels warm and cushioned on the volcanic soil like in a mother’s womb. There is a delicate opera-like elegance about the city, there is also the sound of the speech as sharp as fish scales, there is wine powerful because of the bright sunshine, while the light of the south makes colours look saturated and full. Palermo imprints Mediterranean images, the south invigorates and enchants. We will be younger, faster, lighter, once this trip is over.

One gets carried away by Palermo and Sicily, more than ever now when the world is spinning like a whirling top; Palermo trembles like jelly on a cake of volcano lava colour. One gets carried away by the opera, its music and a story weaved in the libretto about a former pirate, Doge of the maritime Republic of Genoa, by the name of Simone Boccanegra. The performance, just like any story, including those in Arabian nights, delays the death hour, the magic of a theatre spectacle slows down and banishes thoughts of the world’s grand stages for a moment.

After the opera Palermo people will stroll down the promenade, have another liqueur and coffee; pupils are opened by espresso in a Sicilian evening that has begun and is still there. They eat, in a pastry similar to a croissant, an ice cream that is dark green, sprinkled with tiny seeds of pistachio, so teeth feel the softness of pastry and sweetness of the milk delicacy. During the night somebody will get hungry and will have arancini, small oranges, that is how they are called, which are fried rice balls, filled with cheese, greens, butter; teeth will bite into a crispy outside layer and a soft, melted heart.

Again on Via Maqueda I can see the elderly couple, him wearing a three-piece suit and a woolen coppola on his head as evenings are still chilly, her wearing an English cut costume and a floral, girlish amber brooch. He is retelling the libretto for her, the plot which is typically opera, complex and intricate, but she only asks if there will be love intrigues and his answer is:

– There will be, amore mio, there will be.

Translated by Katarina Pavličić