SHIVA’S DANCE IN MONTAGNOLA

By Saša Ilić

April, 2023

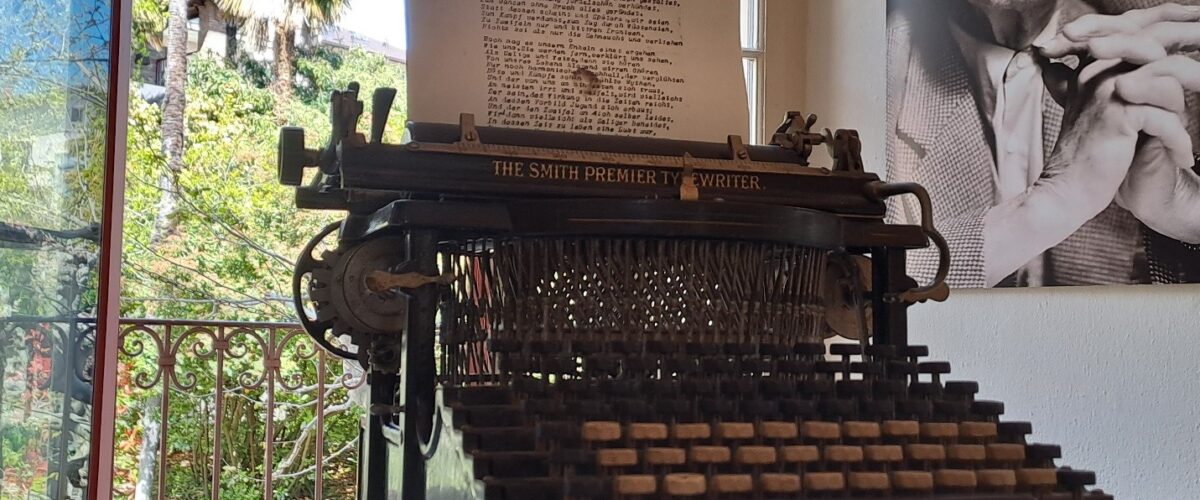

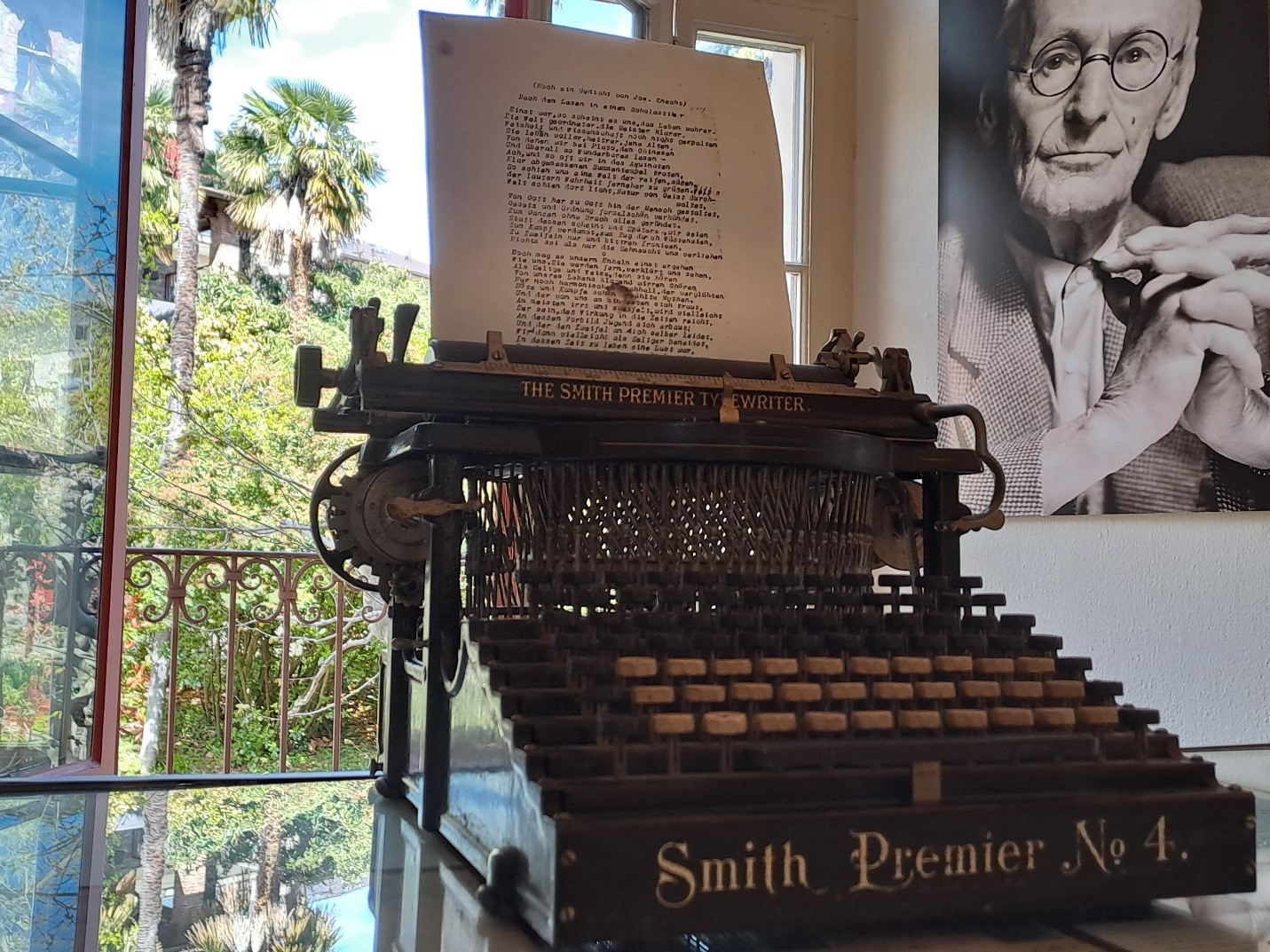

This is not my journey. It is Nadja’s. Just as the voyage to India in 1911 was not Hesse’s but Siddhartha’s. In the same way that Siddhartha’s walk with the Samanas was not his own but Budha’s. When Hermann Hesse, horrified by war and his wife’s illness arrived in Ticino in 1919, he sought the road to the hills and the village of Montagnola up there. Although, he believed the journey to be his own it was that of Siddhartha, because having made the initial few steps out of Lugano he was already treading the paths that led him to write the novel about the Brahmin’s son. Now, what a sojourn in an Italian canton in Switzerland’s south has to do with India when the morning bell rung from the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli is a constant reminder of Christ’s crucifixion conserved on its walls. It was painted by a renaissance master Bernardino Luini, about thirty years after the epidemic of plague in Europe, far from Buddhist meditations and the Brahmin religion. And yet, it was on that road that Siddhartha was written, Hesse’s meditative novel of self-awareness. Although first published in 1922 it gained full actuality only within the hippie movement, after the death of its author. Some books indeed have unpredictable fate, but far more interesting is their link with the ambient wherein they were created. In order to understand that one must come to the very place, where in between footsteps across mountain passes ideas emerged to be transformed into words and, eventually, letters which in afternoon hours rained from the keys of Hesse’s’ Smith Premier No. 4 typewriter onto the whiteness of paper in a downpour of lead.

Nadja and I travelled to Lugano by train from Zurich through a hazy late winter landscape stretching under the low clouds until total darkness set in with only the illuminated display in the carriage telling us what actually happened: we ran at a speed of 200 km per hour under the Alps through a 50 km long tunnel – the longest in the world. A family with children seated across from us continued their game of association in Italian, as if announcing what will happen once we emerged on the surface of the earth and all of a sudden, unaware of whatever happened in the meantime, all around us, in the light of the landscape and the enormous blue sky we glimpse where the Mediterranean begins.

I promised Nadja that on that journey, walking towards grande belleza we would celebrate her eighteenth birthday.

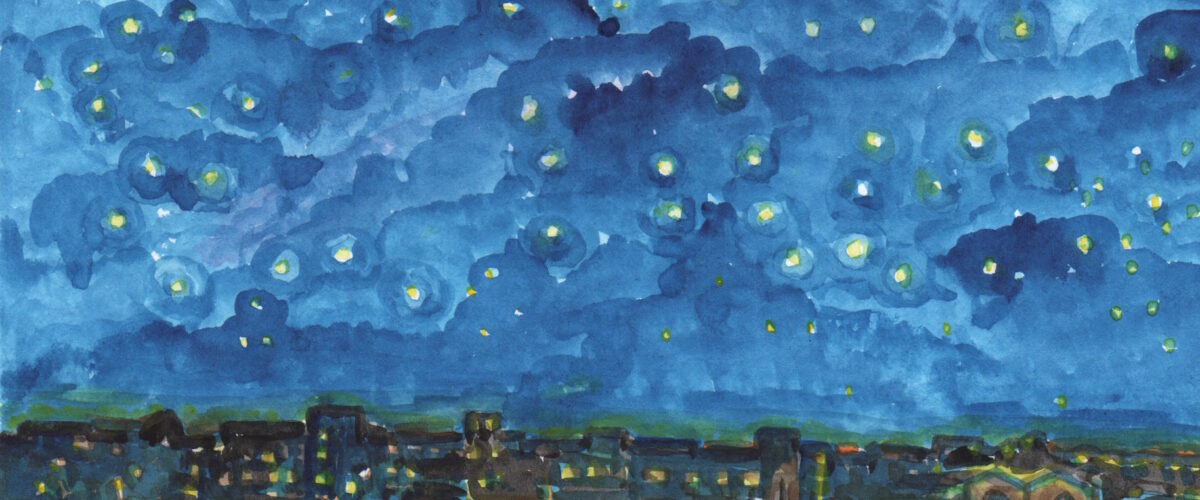

Once the train sets out through a changed scenery towards Bellinzona, mountains lose some of their power and the whole countryside opens to the sun. A traveller observing that from a modern train that safely pulled him through from under the Alps, has the impression that at any moment he will burst out onto a seaside where the northern Mediterranean nested wedge-like between the mountains, in the same way as in the Balkans where, according to Predrag Matvejević, it found its way trailing the paths of rivers and human literacy: the Neretva river and Dubrovnik’s literature. And thus Ticino, that smaragd piece of land, was long ago swamped by the World spirit which found in it its temporary haven. And when it receded, as if after a deluge, it left behind a blue-green Lake Lugano, yellow urban belts and distant blue mountains with their once long lasting snow caps. However, the climatic changes largely altered the topography of the Alps, with the melting of their glaciers almost in its last stage, but the mountains viewed from a distance kept their austerity, although it too wanes away along the road to Lugano.

Why didn’t Hesse remain down there in Lugano, asks Nadja walking by my side? Actually, I have no idea and can only guess. As a guide on this journey, I try to make do with only the most important facts, the indispensable ones. Such as e.g. the number 436 bus we have just disembarked at the Bellevue station. While we stand on a major crossroads in the hills, looking for a road sign, a young woman with her daughter and a dog comes by. I ask her for the route to Hermann Hesse’s Museum in English. She looks confused but soon recovers her composure and tries to explain it to us. At last, she says that it would be best if we walked together for part of the way, as we are headed in the same direction anyway. Her name is Varja. She keeps her dwarf terrier on a barbour leash, but issues her commands to him in Russian. Her indifferent daughter has a perfect British accent. They are obviously part of the Russian emigree wave launched after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Varja belongs to the class that can afford to remain living in Montagnola and Ticino where a square meter of housing costs up to 12.000 CHF. Even renting here does not come cheap. It has been less than a month since the collapse of one of the largest Swiss banks, Credit Suisse, but that does not show on the society’s surface. The state Bank UNS delt with the financial abyss during one cold weekend and none of it has been mentioned in public again. The franc remained stable. The inflow of rich immigrants gave rise to prices just as everywhere else in Europe. That is quite unusual in times of wars, especially such as the one in Yugoslavia, which no one here seems to remember. There was also intellectual migration, but it had no money. On the other hand, potential businessmen drew close to parties in power and remained in the country in order to enlarge their property. Their children were sent abroad to Harvard, Oxford, Yale. Others sold trafficked Dunhill in the streets to somehow make ends meet.

Russian emigrees in Switzerland have no existential worries. Thay believe that after the war they will once again resume their former places. In Montagnola or Rublevka – no matter. Varja, her daughter and their dog Kiril continue their walk, having brought us to the fist road sign with Hesse’s signature. The road is there, or rather one of the paths leading out of the well-ordered village on the slopes of Collina d’Oro (Golden Hill). It may be that the golden shine of this hill attracted the Camuzzi family to move to Lugano in mid fifteenth century, only for one of its branches to mount up to Montagnola sometime later and settle there permanently. A descendent of this family was architect Agostino Camuzzi, whose works survived to this day, bearing in mind that, having worked on designs for the Hermitage in the service of tsar Nikolai he returned from tzarist Russia with money and ideas. Casa Camuzzi was thus created: some call it a palace, others a villa, but it is in effect a mixture of Russian baroque and neogothic elements, resulting from master Cammuzi’s years of learning in the east and his homeland in the west, combined in a family edifice dominating not only Montagnola but entitre Ticino since mid-19th century.

It means Agostino, too, had to travel east, notes Nadja leaning on the fence of a vineyard for a better overview of the road we have covered. Obviously, I say, he went to look for something missing in Montagnola. But what was that, actually? Knowledge, dosh, glory? Well, I say wisely, if we listened to Budha, i.e. Siddhartha or Hesse, we would say that he went in search of himself… Himself? She repeats sceptically, sounds trite. I do not mean himself as such, I try to explain, more like self-realization… Nadja becomes animated, she likes to philosophize: You want to say – one possible self. If young Agostino went to China we would now have a different Agostino, that’s cool. Or still better, he could have gone to Japan. Just imagine Casa Camuzzi as a combination of Japan and Italy – more wood and a curved roof. You read Mangas too much, I say climbing the stairs towards a large gate, entry to the upper yard of Casa Camuzzi, while overgrown terrace gardens cascade down its south side.

There on the junction of Via dei Camuzzi and Ra Cürta, which later on becomes a country road, stands the Museum of Hermann Hesse, with number 2 and his photograph on the stone wall and a round table in front of its entrance. He used to live there on the upper floor from 1919 until 1931. That is where his books Narcissus and Goldmund , The Glass Bead Game and, naturally, Siddhartha where written. Immediately on his arrival, during the first summer spent in Ticino, he wrote an expressionist novella Kligsor’s Last Summer, which conserves traces of the topography of the garden and the house as they were at that time, especially the balcony off his study. Today, that is the centre of the great writer’s museum, with a huge desk and waiting on it a Smith Premier No. 4 with a page as if just typed still in it. It reminds me of a Japanese Akita dog who never stopped waiting for his master to one day come back from his walk and resume his writing where it ended that morning. However, Smith Premier No. 4, a typewriter with double keys for capital and small letters, like the terraces of the park stretching behind Casa Camuzzi, does not know that way back in August 1962 Hesse went for his last walk and did not come back. Otherwise, we would today have yet another book or novella, perhaps a letter, another record about that typewriter which, he said long ago, was as noisy as a steam engine entering a station; but actually, there were only sentences stringing one after the other over the paper on a thick roller. That impression of a lonely wait is perhaps more powerful of all in Casa Camizzi; notwithstanding the multitude of its books, photos and objects from the author’s everyday life, nothing more than this typewriter reveals the absence of the man who used them all, seemingly until recently There are also his glasses, a pair among the hundreds Hesse owned. There is also the bronze sculpture of Shiva, the Indian god in exultant dance wherein he destroys the old order and gives birth to a new one, that which Hesse found during the Great War on the slopes of Montagnola.

Look at him on this photo, Nadja calls me quietly, while other visitors pass by. The guy was totally crazy – he practised Nackteklettern (rock climbing without clothes or ropes) … Is there a book with it? I don’t remember, I say watching the dance of the Indian many-handed god. Today again a world is disappearing on European soil – what awaits us after Shiva’s dance? That is what the refugees from Ukraine wonder, those I see on the windows of the former nunnery between Zug and Oberwille. At dusk, when a torrential spring rain pours down, they close the windows and withdraw into the dimmed light of their refugee lives. The guy definitely was not good with women, says Nadja pointing to a series of black and white photos from Hesse’s private life. His first wife, Mia Hesse became mentally ill after her third childbirth and they divorced before his arrival in Ticino, distributing their children all over their family. Omg! Then the second one, Nadja softly continues to read the captions under the photos – a certain Ruth Wenger… Again, misunderstandings and a year and a half long therapy with Jung – well, Nadja smiles, at least he had an excellent shrink – ahhaaa…, that was actually at the time when he wrote Siddhartha… Thus, leaving all the Buddhism aside, what is left is an unhappy marriage, three broken children, another dysfunctional relation… And what else, she repeats sliding her finger between the photos… what else…? What remains is Montagnola, I say. Oh, no, disproves Nadja, there is the mental issue of Frau Mia Hesse… That, I think, would be a topic for a good novel…But no, he met a certain Ninon Dolbin and they lived happily ever after… I think, she adds, that after the 1945 Nobel prize, it was not all that difficult. It was not all that simple, I warn her while looking at Hesse’s water colours where Montagnola seemed to find a kind of a different life, composed of colours and feelings of freedom: It was not easy to oppose Hitler, save the exiles, here in Ticino, and Hesse did that. Somebody waited for these wretches in Montagnola and provided them with temporary shelter. That’s right, and he did not charge them 2000 CHF for a night, she adds ironically. No way, I say, many a known and unknown person went through this house including Peter Weiss, author of The Aesthetics of Resistance, who escaped the occupied Sudetenland in 1938. How can resistance have aesthetics? Asks Nadja. It can if literature deals with it, I contrive. Resistance is a matter of politics and ethics she puts me right. Occasionally it is also a matter of literature, if someone can write about it, I say, trying to recall who in our parts wrote about it in that way and survived Perhaps – Davičo.

In the centre of Montagnola, immediately behind the Museum there is a Boccadoro Literary Café – or At Goldenmouth’s, a name inspired by Hesse’s novel, just as the entire ambience from the garden behind the yellow arches to the interior of the caffe bears the mark of his literature. Naturally, the cover of the drinks menu boasts Hesse’s picture with a raised glass, as if ready to make a toast, which he actually did writing about [the god of] wine in 1832: Who is as mighty as he? Who as beautiful, as fantastic, lighthearted, melancholy? He is hero and magician, tempter and brother of Eros? Perhaps only a good wild pear brandy, Nadja laughs while spontaneously ordering Spritz Aperol from the menu. Our eyes meet for a moment and she smiles? So, what, I am turning eighteen right, so I can take a little spirit, that is if prosecco counts. Of course, I answer and nod to the waitress confirming that I will have the same, but the birthday hour has not come yet. No, it has not, she confirms, but soon it will. That is best felt on a journey, I say, a limit in time is just as vague as in space.

Hesse wrote that in Montagnola vita activa ceases and vita contemplativa begins, but exactly at what point is yet unclear. I think he was tripped out, says Nadja, expectantly awaiting the arrival of our waitress with a piercing in her left nostril. When Spritz Aperol arrives we touch our glasses across the table and toast our day in Montagnola. Spritz is disappearing fast and so we order another and a piadino with prosciutto and mozzarella.

After lunch we walk along the streets of Montagnola, no longer following Hesse’s road signs, but our own intuition, a compass showing us direction towards our own selves. We pass above the houses undergoing renovation, below cranes lowering construction materials into the yards of weekend houses; their rich owners hidden behind sunglasses rest in reclining chairs. Below that the vista opens on vineyards, and then wavy meadows where, at times, a flock of birds fakes off startled by our presence. Montagnola remains behind us, but we clearly feel that the slopes of the Golden Hill are still there, the deceptive border between walk and contemplation stretches out as that time between late childhood and maturity. Having climbed a rocky crag we stop and look at the view opening before us in the vastness below Montagnola. Down there is Lake Lugano, surrounded by blue mountains and green hills, while high up in the endless Mediterranean skies slide invisible shadows of times past – the scent of nature has filled every photon brought to us on the wind from the Alps. Behind us are also the herds quietly roaming the meadows. Some of the cows occasionally wonder out of the fenced pastures into parts of Ticino such as the lonely cemetery Gentilino near Sant Abbondio church with its bell tower aligned with dark cypresses. Under these trees Hesse’s grave remains; close by lies Hugo Bali the inventor of DaDa, his wife Emma at his side, just as during their lives. Further on towards the older parts of the cemetery stands a modest monument to master Agostino Camuzzi, who remained there in constant expectation of occasional, and increasingly infrequent visits of his daughter.

But the two of us are turned towards the valley – city and lake. Towards the deep colours pouring down the slopes of Callina d‘Oro. Mere thirty or so kilometres from here is Como, I comment more for myself? Italy, grande bellezza, Nadja and I exchange looks. I wish you’d remembered this moment, I tell her, that is my gift to you. She merely nods and tightens the straps of her backpack. Then, as if by design, we take a few stops back and spontaneously run towards the edge of the rock ending in a steep drop: as if it marks the beginning of a huge vastness of air plunging towards the inert blue of Lake Lugano between the mountains. Nadja and I take a leap towards it and remain there as in a freeze frame.

Text and photos: Saša Ilić

English translation: Ljiljana Nikolić

About the author:

Saša Ilić, born in 1972. in Jagodina, graduated at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade. Published three books of stories: A Presentment of Civil War (2000), Dušanovac. Post Office (2015), Urchin Hunt (2015) and 3 novels: The Berlin Window (2005), The Fall of Columbia (2010)and The Dog and the Doube Bass (2019) which earned him a NIN award. One of initiators and editors of Beton, a literary supplement to the daily Danas from its start in 2006 until October 2013. In December that year he and Alida Brenner jointly started Beton International issued periodically in German as a supplement to Tageszeitung and Frankfurter Rundschau. Member of editorship of International Literary Festival POLIP in Priština. Translations of his prose are available in Albanian, French, Italian, Macedonian and German languages.