Lover of the Eye

There is only one city on this planet that is a vestibule of the other world, that lies like a human embryo submerged in opaque-crystal water, and whose changeable face burnishes its own reflection in millions of mirrors: Venice. It is a city with innumerable disparate window eyes, with buildings permanently afflicted with an incurable skin disease caused by the water’s incessant noisy touch as it laps at their walls with dark, wet kisses. It was my father who first brought me to Venice – I remember us entering the city hand in hand, and its heavy breath mingled with the sleep of thousands of pigeons, which hovered above us hypnotically for hours. That first night, after an evening spent in a strange transcendental daze, full of warm, fragrant rain and shallow, sad gondolas, I dreamed only of mirrors. Mirrors that spoke, kissed, laughed and begged for the mercy of death, and a monotonous voice that replied: ‘You are condemned to immortality.’ In the morning, I set out on a quest, a hunt for the lustrous world of delicate, crystal creatures – a search for mirrors.

If the profile of Venice is made by the swaying opiate of water, its interior consists of mirrors; as does its memory, since mirrors are unable to forget. Thus, they know no consolation. I remember a mirror that beautified everyone who stood in front of it, that erased the filigree marks of time on human faces and dispelled the halitosis of living matter that breathes, blooms and decays all at once. Visitors stood in front of that mirror for hours, and it embellished their faces in a faint haze of infinity by adding the clemency of Christian icons and the calm, carefree wistfulness of the portraits preserved in Pompeii. The magic was complete: the mirror widened the cheekbones of narrow faces and brought a tipsy ebullience to sad eyes. ‘I come back every year,’ a woman whispered, ‘I’m in love with the one in the mirror.’ ‘What’s the mirror called?’ I asked a guide. ‘Venetian,’ came the curt reply before he vanished into a dark passageway.

Pasternak claimed that Venice resembled a ‘swollen croissant’, while Brodsky, who visited at Christmas for years and later decided to be buried in a Venetian cemetery, thought it looked most like ‘two nearly overlapping lobster claws’. Erica Jong, also an obsessive Venice visitor for years, describes it as ‘the place that traps tortured spirits. It is the flypaper island. It must constantly have new blood to replenish the old. Venice herself is no more, no less, than a vampire.’ Predrag Matvejević, after one of his countless visits to this city like a living dream, wrote: ‘The rust of Venice is sumptuous; the patina like gilding.’

Venice is a ‘giant liquid mirror’ this summer, too, where tourists throng in front of palaces, colonnades, arcades, angels, mosaics, ornaments, marble lace, balconies and cherubs eroded by the damp; they stagger from the beauty, heat and lavishness, together with the shadows of the dead, which here alone are kind, bright and of firm step because Venice’s degree of beauty relativises real life and annuls death, and the water in the canals retains the reflections of all of us who have flocked to the city like pilgrims. Byron wrote Don Juan here, George Sand and Alfred de Musset loved and cheated on each other in these narrow streets, Thomas Mann composed Death in Venice on the island of Lido, and Hemingway drank in Harry’s Bar. In Caffè Florian, you can still hear the shades of Marcel Proust, Dickens, Byron, Wagner and others breathing heavily in the corners. Inside, everything is covered in theatrical burgundy plush – including the walls, of course.

In the 1950s, Auden drank espresso and cappuccino here with his greatest love, the unfaithful Chester Kallman, and Stephen Spender with his wife. Brodsky swore in his youth that if he ever managed to escape from the then Soviet empire he would first of all travel to Venice, ‘rent a room on the ground floor of some palazzo so that the waves raised by passing boats would splash against my window, write a couple of elegies while extinguishing my cigarettes on the damp stony floor, cough and drink, and when the money got short, instead of boarding a train, buy myself a little Browning and blow my brains out on the spot’. Of course, when he first rushed to Venice, he was sent by Eros. He waited in the fog for a Venetian woman: tall, with eyes the colour of jade or honey, dressed in suede as thin as cigarette paper – and married. That love never happened and Brodsky called it ‘a betrayal of the fabric’.

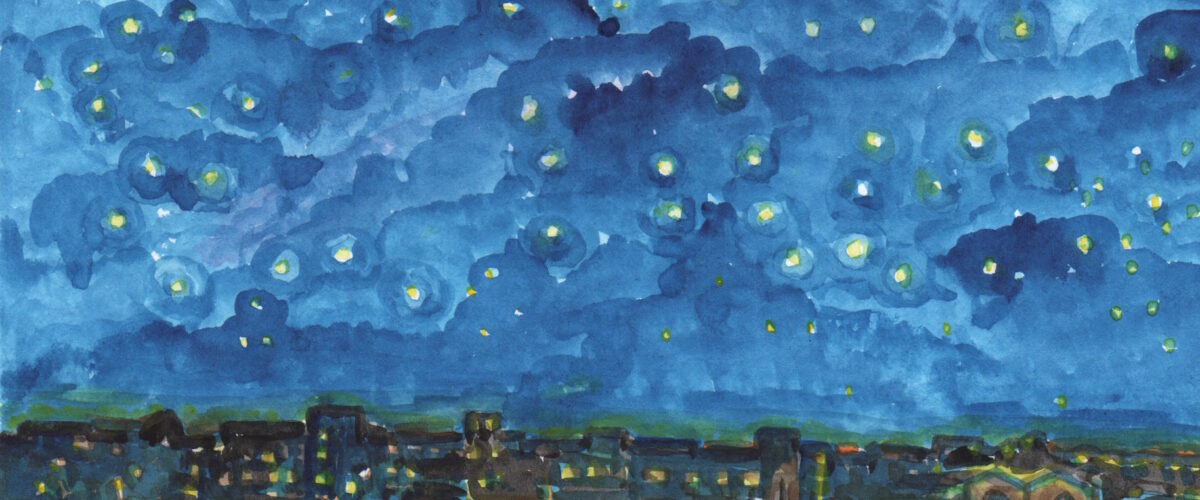

This city causes turmoil and something deeper than love in every visitor, and the baroque and Gothic façades, whose reflections flicker in the water, elicit a primal shudder in people. The human body is made up largely of water, which is why terra firma is not the most comfortable place for human habitation. ‘The only thing that could beat this city of water would be a city built in the air’, Brodsky wrote. Venice, that ‘lover of the eye’, even annuls death, which here resembles an endlessly long dive. Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Pound and other famous figures are buried along with Brodsky in the Venetian cemetery of San Michele. They rest here forever, beneath a grapeshot of wispy clouds that drift across the sky and look like a musical score (the head of the moon is the head of the bass clef, and the head of the sun – that of a violin). Less famous denizens are exhumed after twelve years and buried in a common grave. But the Venetians themselves do not like to talk about this. There are a multitude of famous ones, as if genius spouted here at every turn and was itself narcissistically attracted to water, in which it could be reflected. The Venetian Antonio Vivaldi was christened in a small, pink church as a premature baby. His parents arranged an emergency baptism for him, fearing he would not survive. But fate had different plans in this realm of water and light. Music, water and light go together like triplets, and Vivaldi grew up to be a virtuoso and composer under the patronage of the first. The inaugural Vivaldi Week in Venice was organised by Olga Rudge, Ezra Pound’s mistress and muse. Once, while performing a long piece with many complicated passages, she had to play and turn the page at the same time. At the right moment, a hand appeared in front of her and slowly turned the page. ‘That is how I first met Stravinsky,’ she said later.

Brodsky and Susan Sontag once visited Rudge, who droned on about Pound’s true political convictions and stressed that he had been misunderstood. Sontag listened, whereas Brodsky admits having concentrated on the biscuits. Seven centuries earlier, the eighteen-year-old Venetian Marco Polo left for the Far East. He returned many years later with something the Italians would see as long, narrow tubes: spaghetti. That is how an indispensable part of Italian cuisine arrived in Italy. Luigi Da Porto (d. 1529) was also a Venetian, and he would certainly have been forgotten if he had not written the story of Romeo and Juliet. Sixty-six years later, this theme would be adapted for theatre and exploited by none other than Shakespeare.

The Venetians themselves are reserved and distrustful of foreigners. (Venice was ravaged by the Plague three times and caution towards what strangers bring to the city has become ingrained in the locals’ makeup.) The famous Venetian palaces are mostly uninhabited today because they are owned by magnates who come only to spend a few weeks a year. One can seldom enter any of those buildings, whose walls seem to be afflicted with a rare skin disease. Inside, visitors are met by a series of rooms that continue one after another, an enfilade that becomes darker and darker the further you go. Only occasionally, when your guide raises their candle or torch, do you glimpse the curls of cupids or the passionate eyes of saints. The owners themselves often do not know who painted those magnificent images, which live without light, like deep-sea creatures beneath the waves. Perhaps the artist was even Titian, one of the residents of Venice carried off by the Plague. The city on the water often burned, since the elements of water and beauty attracted a third: fire. The opera house La Fenice – where the debut performances of Verdi’s La traviata and several of Rossini’s operas were held – burned down repeatedly, the last time in 1996. It was promptly reconstructed. The Doge’s Palace, where the double agent Casanova served a prison sentence, burned down four times. The most interesting part of it is seldom opened. Behind the bookcases of the Palace library, a secret passageway leads to rooms on the top floor, where doges’ assistants concocted accusations and filed secret documents, far from the public eye. From the outside, this part of the palace seems not to exist. The secret parts also house a torture chamber, with one single device: a rack. Here are also the stairs down which Casanova managed to escape together with another prisoner, who had inclinations similar to his own – and was a friar.

Venice’s outward resplendence inspired Veronese, Carpaccio, Giorgione, Bellini, Titian and Tiepolo. Countless paintings are at home in Venice, and painstakingly preserved, although the walls of the Academy of Arts with the most complete collection of Venetian painting also bear the pale watermark of damp; I always remember the large, recently restored canvas by Veronese, The Feast in the House of Levi, which he began in 1573 as The Last Supper. The Inquisition forbade the painter from exhibiting it because of the dogs, dwarfs and drunkards in the painting. Veronese did not change anything except the name, and so the painting survived the Inquisition. This summer, as I was wandering through this forever cavernous city, I thought of Akhmatova, who claimed that Italy is a dream that keeps returning for the rest of your life. Whenever the author of these lines dreams of Venice, it is a suburb of another world – the other world.

Like everything magnificent on this sinful earth, Venice is not what it seems at first glance: Eros does not rule here, although one imagines he always goes hand in hand with beauty; this city loves solitude and loners, and it is most beautiful in winter, when there are the least tourists. Also, this is hardly a city suitable for honeymoons (a Venetian woman poisoned her husband, the king of Cyprus, on their wedding night in the fifteenth century, and so Cyprus became part of Venice). ‘It should be tried for divorces also,’ Brodsky suggested, noting that Venice is a city where you can never get enough sleep, and whose beds with all their lace and satin make it hard to sin. Here, the eye makes love with the city. The body behind the eye just staggers through the lanes reminiscent of the labyrinths from the first night after death.

Sanja Domazet

Translated by Will Firth

Photos: Bogdan Trifunović