Sweet Travelogues – The Unforgettable Taste of Serbia

Slatko, a traditional sweet preserve, is a delicacy made from well-cooked fruit, certain types of vegetables, or edible flower petals in a highly concentrated sugar solution. It was mandatory to serve it before coffee in Serbian cities for over 200 years. It was the first morning serving for all household members, taken with a glass of water, and was mandatory refreshment for guests, both daily and especially during holidays. Slatko was also eaten as a dessert when there were no cakes in the house. Above all, it was served to guests as a sign of welcome and respect, heartfelt hospitality, as a representation of national identity and especially Serbian civic culture since the mid-19th century. A jar of slatko was given as a gift on special occasions as a very precious and valued present, which was specially preserved, and there is a popular saying: “Slatko starts the day!” which speaks of this serving ritual as a sign of success and good manners towards oneself and others. Slatko is a faithful companion of cultural development, representation, and the symbolic value system of modern Serbia after liberation from the Turks. One of the oldest domestic “brands”, and simultaneously a great unofficial diplomat, alongside šljivovica plum brandy…

The predecessor of slatko was fruit preserved in honey, which came from Byzantium to Serbian medieval cuisine. With the discovery of sugar and its industrial production, the preparation of slatko began in the Mediterranean. Slatko is prepared by Greeks, Cincari (Aromanians), Jews, Macedonians, and Bulgarians, with the Sava and Danube rivers forming the northern boundary of this delicacy’s distribution. Muslims in cities did not adopt this custom, while in Vojvodina only compote was cooked. Turks traditionally served ratatouille and hookah with coffee. As mandatory refreshment, slatko was characteristic of Serbian urban homes until the mid-20th century when rural populations adopted it, mastered the cooking art and transferred the technology to villages, as fruit was abundant there, and life in cities was changing, just as production was changing. The custom, though increasingly rare, has been preserved in villages to this day, while in cities – as the poet Duško Radović ironically mentions in the cult show “Good Morning Belgrade” – slatko has been pushed to the periphery: “It’s time for slatko and water, which are still served only in underdeveloped and backward parts of the city.” Paradoxically to this quiet extinction of this essential daily custom among Serbs, there are numerous accounts of fascination and respect that slatko aroused among many world travellers, diplomats, artists, and official guests who visited the Serbian principality and subsequent kingdom during the 19th and first half of the 20th century.

Slatko as a fragment of Serbian hospitality often found itself at the center of attention of both domestic and foreign guests. This special delicacy, “neither compote – nor jam – nor honey”, attracted great attention from travel writers and diplomats who travelled throughout nineteenth-century Serbia on various missions, and even later, when this product became common in our region, it was written about as a rare and precious delicacy for which a traveller’s hand would always carelessly or unknowingly reach at least once more. As they themselves vividly testify, this often happened multiple times until the sweet treat was completely gone. “While the queen was talking about the painting, a footman entered the hall with a silver tray carrying a large crystal vessel with that excellent fruit compote that in Serbia they call slatko. The compote was sweeter than honey.”

The first woman who independently prepared and served slatko in Serbia was Princess Ljubica, who, as the “supreme housewife” in Ljubičevo, as described by Felix Kanitz: spun wool, kneaded and baked bread, and cooked slatko. Even as a young girl, she served the elderly and infirm, as evidenced by an article by the early deceased Prince Milan M. Obrenović published in the magazine Uranija in 1838 titled “Children, You Too Will Grow Old When the Time Comes”. Her personal qualities helped establish slatko as a significant fragment and symbol of the finest social ideals and national characteristics. It also became part of the official protocol at the Serbian court. Queen Natalija Obrenović taught officials how to properly serve this product, which was presented with special care at the court, as the home of the Obrenović family. This was true in every other Serbian house, inn, and hotel; the delicacy was proudly and kindly served to guests, and was even brought when prominent people happened to end up in prison, which Kanitz also noted during his visit to Požarevac. On Kopaonik, he describes a breakfast where the youngest daughter bid him good morning, kissed his hand, and after a glass of cold spring water, brought out: slatko, rakija, cheese, milk, and black coffee. In Jagodina, the famous writer and ethnologist visited the “Lacko Janković” factory, which was already producing special vessels for slatko, as well as pitchers and glasses, later shipped to Belgrade to be sold in Vuk Karadžić Street, where they were in high demand.

“All our Serbs from various regions, when they visit us, cannot praise our slatko enough. And not just Serbs, but also numerous foreigners who come on business to visit our prominent people describe in their reports how they were served excellent slatko and a glass of water, and how much they liked this custom”, as Dr. Radivoj J. Vukadinović recorded in the magazine “Woman” in 1912. The tradition of “compote sweeter than honey, a beautiful Serbian custom, the first hospitality and Serbian specialty, so good, tasty and beautiful that it could without exaggeration be compared to the best sweets in the West”, was continued by the Karađorđević family. At Prince Alexander’s court, Captain Miša Anastasijević finds it in the formal salon alongside the clearest water and coffee. Similar experiences of shown honour and unforgettable taste, which made hands reach several times beyond protocol and custom, were shared by: Sava Bjelanović, Vlaho Bukovac, Otto Dubislav Pirch, Adolf Smith, Andrew Archibald Paton, John Palgrave Simpson, Albert Malet, Count Adolfo of Caraman, Siegfried Kapper, William Denton, Rista Prendić, Pavel Apollonovich Rovinsky, Grigory Nikolayevich Trubetskoy, and finally Aleksandar Deroko and Momo Kapor couldn’t imagine returning to Belgrade and Serbia without that spoonful of “little golden sun”. Whenever they tried to revive childhood memories, traveling in thoughts to more tender days, there would always be someone’s slatko made from cherries, sour cherries, quinces, watermelons, figs, blackberries, stuffed plums or roses, even oranges, over which two of the world’s greatest minds, Mihajlo Pupin and Nikola Tesla, reconciled. Along with descriptions of elegant serving, there is always notable mention of Serbian women and housewives who independently and ceremoniously undertake this mutual honor. Serbian slatko is also mentioned as “omnipotent”…

“Gentle-blooded Serbian women” in the middle of the Balkans left an impression of exceptionally orderly, skilful, elegant, and proud women who inspired admiration and respect. Their trademark was the art of cooking slatko, and wherever a traveller would pass, a small unforgettable ceremony awaited them. “Her apartment was shining with cleanliness, and in the morning she served us the first Viennese coffee with whipped cream, which I hadn’t drunk in a long time. It was evident that she tried to host us as best she could… Before coffee, as soon as we woke up, following Serbian custom, she offered us slatko with water. The slatko was delicious, and when we were leaving, the hostess forced us to take two jars… And when I gave each of her children a gold coin to buy themselves a toy, she turned red as a lobster at the thought that I wanted to pay for her hospitality.”

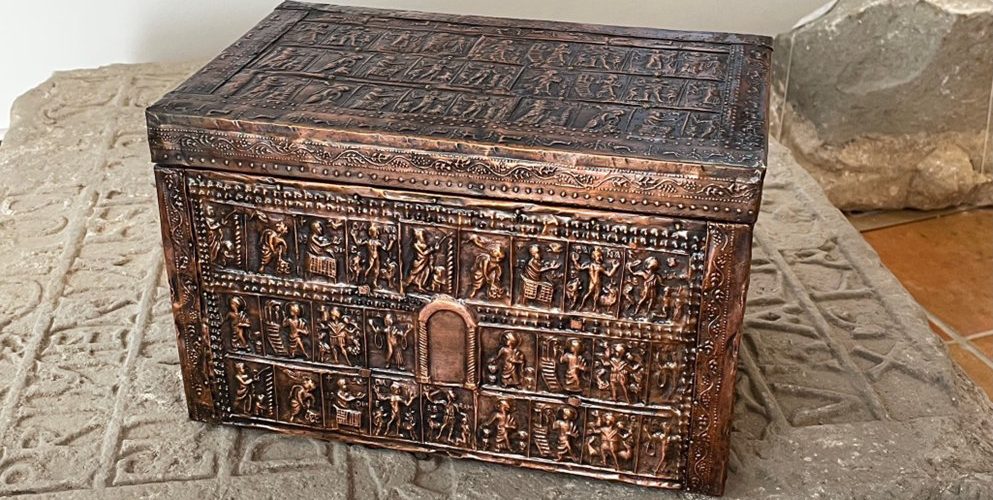

The tradition of slatko in the Cvetić House in Kraljevo, today’s “Museum of Slatko”, has been maintained since 1908, since merchant Filip Cvetić opened a wine and rakija cellar, and then supported the opening of a colonial goods store regularly visited by French aviators along with Louis Breguet, director of the Royal Aircraft Factory. Filip’s great-grandson with his wife and daughter, an art historian and theorist, revitalized the house and craft, forming an authentic collection of items for serving this delicacy, as well as other collections that testify to the everyday culture of civil Serbia, especially its intangible values. Through the interpretation of family heritage and professional practice, the Cvetić family has been dedicated to museology since 2010, and the number of various slatko varieties has reached 45, made from fruit and wild flowers from the historical garden. The “Museum of Slatko” is a member of the European Historic Houses Association (EHHA) based in Brussels, as well as ICOM Serbia. Instead of showcases, in the formal salon, painted in al secco technique, there is a credenza with trays, starched doilies, liqueur glasses, silver spoons and slatko saucers, as well as a cabinet for the edible museum collection. The Cvetićs live with their heritage, not disrupting ancestral practices, and alongside research and exhibition, they place special emphasis on educational and creative museum practices. Like Proust’s madeleines, in search of lost time, the smells and tastes of Serbian slatko lead us on a nostalgic journey to the past, to the time when we were forming modern Serbia and sent messages to the world through our collective cultural paradigm. Travel writers’ notes testify to the importance of this small, historical delicacy that opened our path to deciphering the specific culture of our region. A “strange land, far from the paths of ordinary travellers”, through hospitality and unique delicacies, opened its doors to the senses of researchers, writers, merchants and educators, clergy, diplomats, scientists, adventurers, and above all, worldly hedonists, which they all were to some extent. Sometimes, not surprisingly, due to fatigue and hunger, they would stray from marked paths, but on the unpredictable trails of Serbian gastronomy. Before every dinner or breakfast, a lacquered tray with slatko awaited them, which reminded them like nowhere else in the world that they were welcome. This unforgettable feeling about Serbia is what we regularly revive at the “Museum of Slatko”.

Dr. Lidija Cvetić Vučković

Creative Director of the Museum of Slatko, Kraljevo

August 2024

Photos: Museum of Slatko, Kraljevo