Navigating on the Drava River through time…

Living alongside the jungle of the Drava River is incredibly exciting, especially when you immerse yourself in its flow and its changes it will surprise you every year. In its depths lie numerous stories and treasures that resurface whenever the water level drops and stabilizes, sparking the imagination. This is exactly what the stranded raft of the old mill near Donja Dubrava is doing.

Not only does life of all kinds thrive along the river (more on that later), but near this location, there have been repeated instances of construction, fortification, expansion, destruction, and burning, followed by rebuilding and demolishing again—not just bridges but also much larger and more significant defence and economic infrastructures. According to archaeological findings (in Varaždin, Vularija, Orehovica, Prelog, Goričan, Donji Vidovec, Sveta Marija, Legrad), the ancient Roman road that followed the river’s flow and connected Poetovio (Ptuj) and Mursa (Osijek) passed through this area. The Zrinski family played a crucial role here in defending Europe from the powerful Ottoman forces in the 16th and 17th centuries. In more recent times, the colourful history of navigation and bridging the Drava River in this region has been harnessed by its latest hydroelectric power plants.

Although there are only three hydroelectric power plants on the Drava in Croatia (and the only three in northern Croatia): HE Varaždin from 1975, HE Čakovec from 1982, and HE Donja Dubrava from 1989, this river is actually bound by the largest number of installed hydroelectric plants when you include 11 of them in Austria and 8 in Slovenia.

So that time does not erode the numerous stories of the Drava into oblivion, it would be worthwhile to experience the collected photographs, maps, and stories accessible via the keyword “Filigran Drave” HERE, with this text serving as a companion guide.

Although today’s maps might initially suggest that the Drava connects everything in a single line of flow, the gathered photos and stories are “panned” not just in its main, now sole, channel. They are found throughout the numerous former river branches, whose traces are still visible in today’s satellite imagery, in the terrain’s relief, and are accurately recorded on historical maps. These traces extend even further, connecting the local population into a unique life story along the river, which shaped people´s daily lives, customs, and identities in this region.

Our journey begins in the western section where the Drava River enters Croatia, and we let the river carry us about 80 km eastward to the entrance of Podravina and the former Croatian vineyards on Legrad hill.

As the first indicators of the suitability and antiquity of life along the Drava River, we can consider the proximity of the Homo sapiens neanderthalensis site in Vindija Cave, on a slight elevation of 275 meters above sea level and just 12 km south of the Drava. Also, near our starting point in Borl, Slovenia, a fairytale medieval castle perched on a high rock seems to cautiously oversee river navigation. The “Tvrđa” fortress in Osijek is the next preserved historical-cultural structure directly on the Drava’s banks. Due to the sheer strength of the river itself, this is for the better, as this river can not only flood settlements but relocate entire villages from one county to another, as it did with Legrad in 1710 when it swelled and cut a shortcut to its next meander.

The oldest vessel found from the Drava is in the Koprivnica Museum. It is a massive dugout canoe (monoxyl) made from a single piece of a tree trunk, at least 150 years old, 12 meters long, and 1.5 meters wide. However, the one that left the most significant mark in the area we are “navigating” was part of organized river navigation in the 19th and 20th centuries for the production and transport of wooden construction materials. The navigation covered a distance of about 170 kilometres from Dravograd and Maribor, with a stop at the pier in Donja Dubrava. After processing at the Ujlaki – Hirschler and Sons sawmill, the journey continued for another 220 kilometres to Smederevo in Serbia. The timber being traded was actually also the vessel used for travel. Built rafts, known as “fljojs,” up to 6×25 meters in size and weighing over 100 tons, were navigated only by the most skilled and courageous man. The helmsman, familiar with every whirlpool of the Drava, oversaw and directed the work of the lead raftsman and the rest of the crew. Over time, physical barriers like dams and artificial river regulation, along with Croatia’s connection to the European railway network (1860: Budapest – Nagykanizsa – Kotoriba – Čakovec – Pragersko), as part of economic progress in the first half of the 20th century, completely ended timber rafting as a form of transport. The last demonstration voyages of such rafts were organized by the people of Donja Dubrava in 2013 from Donja Dubrava to Legrad and in 1968 as part of a larger regatta or so-called “Caravan of Friendship” from Maribor to Barcs.

In addition to these unique log rafts, the vessels that preceded the bridges and were essential for the migration of the local population across the Drava were ferry rafts. These ferries were positioned at their permanent locations, capable of simultaneously transporting up to four horse-drawn carts from one riverbank to the other. The speed of crossing the river during high-traffic times, such as agricultural work and harvesting in neighbouring Podravina, would result in waiting lines and socializing while waiting and travelling. Ferries were even operated at night, and navigation was stopped only during winter ice and low water levels.

Another form of transport on Drava was offered by the Donau Dampfschiff Gesellschaft, which operated passenger lines in the 19th century, connecting this region from Legrad to Osijek. Steamships symbolized a new era of mobility and commerce along the river, blending industrial progress into the natural landscape of the Drava. This is why the first visit of the steamboat to Donja Dubrava in 1885 was also composed into a song, here performed by the renowned Lado Ensemble: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsWbZ08cO6o.

Today, navigation is mostly carried out with rubber boats for tourism purposes in the remaining natural sections of the river, as well as with specific traditional wooden boats called “čon”, used by the so-called Drava “wolves” to collect driftwood for firewood or fishing. In the past, fishing and navigation were essential for daily life and work. People navigated the river to collect willow branches, firewood, or to reach the fields, and fish were caught not only with hooks and nets, but also with spears, baskets, and even by bare hands. With today’s modern food supply and transportation, fishing and navigation on the Drava River have become primarily recreational activities—an experience few can resist.

Ferries mostly operated until the 20th century at locations where bridges were later built—Varaždin, Prelog, Donja Dubrava and Legrad. In Međimurje, the first bridge over the Drava River was built near Varaždin during the reign of Empress Maria Theresa. It was constructed as a pontoon bridge, disassembled and reassembled during the passage of the timber rafts (fljojs) or when the river froze in winter. Because of the ice, the river navigation mostly occurred from April to October. Then, by order of Emperor Joseph II, a fixed wooden bridge was built, the opening of which he personally attended in 1786. The next wooden bridge was built in 1953 in Donja Dubrava with the experience and manpower of the local people (supervised by master A. Stančin from Prelog). Later on, in 1977 and 1982 the current concrete bridges were built and opened in Donja Dubrava and near Otok. Wooden vessels and infrastructure often needed repairs or protection due to floods and ice floes, as depicted in photos of the Donja Dubrava bridge from 1964. From the original three crossings, which frequently changed form and functionality, we now have six permanent road- and rail crossings over the Drava River, thanks to the subsequent construction of reinforced concrete and steel bridges. Alongside numerous photographs, physical remnants of former bridges are visible only in a few places, such as in Donja Dubrava, right next to the present-day road bridge.

Other unavoidable structures on the river, which also carries a humorous folk song and faced threats from floods, were the mills. According to a rough count, about 50 mills once operated along the 60 kilometres of the Drava River in Međimurje County. The mills were not fixed and their locations changed according to the water current and floods. Interestingly, they were installed not only on the Drava River but also on streams (Trnava, Dravica, Koprivnica) with sufficient water flow. Today, about 40 kilometres of the river’s flow have been taken over by dams and their reservoirs. The flow in the former natural course of the river has been reduced from the possible 400m3/sec to the so-called biological minimum of just 8m3/sec, and there is not a single mill left on the remaining 12-kilometre stretches that at least demonstratively turns its wheel and grinding stones. In Međimurje, the only mill thats working and is used for presentation is located at the northernmost point of Croatia on the Mura river, which is also the northern natural border of Međimurje and, thus, Croatia.

Međimurje, as a region between two rivers—the Mura and the Drava—is called an island by its modern name, and the same characteristics were carried by its historical names such as Insula inter Muram et Dravam, Insulae Muro-Dravanae; Isola Della Mura e Zeriniana.

On this island, in the last part of our journey from Sveta Marija to Legrad, the river finally enters its untouched course towards Osijek after the last hydroelectric power plant. Here hides the place of people who, until recently, performed perhaps the most exciting occupation along this river. Even if it wasn’t the most exciting, the solitary life, the difficulty, meticulousness, and questionable profitability of the job made it almost Sisyphean, but with a quiet, persistent purpose – the search for gold.

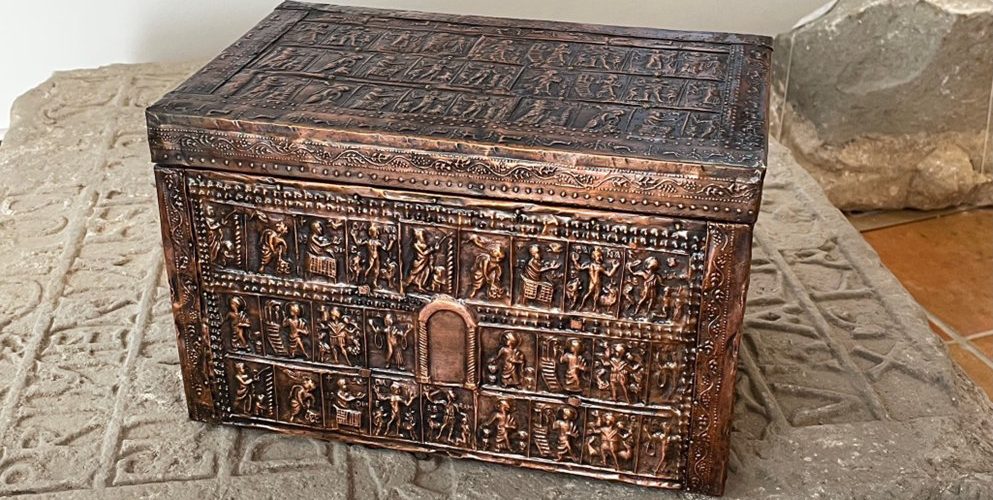

From these villages, especially from Donji Vidovec, goldsmiths (more precisely, gold washers) would spread along the Drava in search of golden sand hidden in the gravel. They would go in pairs for shifts lasting three weeks, covering about 40 kilometres or more. They were often spending the night right by the Drava after exhausting days of shifting gravel and returning with, perhaps, 20 grams of gold wrapped in a handkerchief. By shovelling 10 cubic meters of gravel daily and going through a fine separation process, they could find up to 3 grams of gold with a purity of 23 karats. The value of this gold is confirmed by the washing permit granted by Empress Maria Theresa in 1776 to the goldsmith guild from Donji Vidovec. It can be said that a “gold rush” took over this area at the end of the 19th century when there were 250 pairs of gold washers working here.

Gradually, in the 20th century, the dams prevented the natural erosion of the river banks and therefore the appearance of the new gold sediments. Together with agrarian reform and industrialization, gold washing at the Drava River gave way to more profitable and easier jobs.

It is time to disembark here for now to let the impressions of these once-exciting voyages settle. But I invite your curiosity to our next exploration journey, where we’ll dive into the rich ecology of this unique island between two rivers—because, without the Drava’s natural heartbeat, none of these stories would have existed in the first place.

Kristina Pongrac